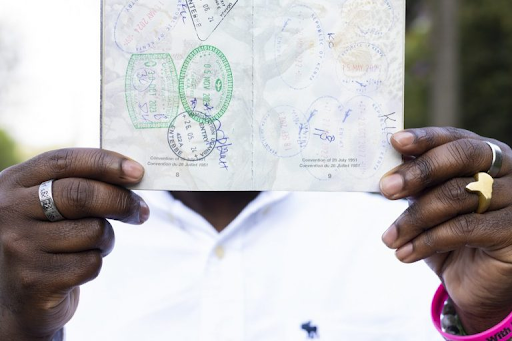

At the Africa Forum on Displacement (AFD) 2025, attendees were given passports instead of typical conference badges. This “Passport Experience” was an immersive simulation designed to give participants firsthand knowledge of the complex challenges surrounding African labor mobility, particularly for forcibly displaced people. Delegates applied for a job in a hypothetical country, and their success depended on the passport they were given and other unseen factors like qualifications and language skills.

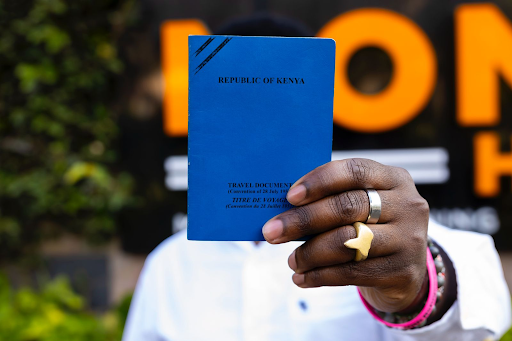

The results were a stark reflection of reality. A majority of participants, 63%, failed to secure a job. Of the 37% who succeeded, 100% held a “blue passport,” demonstrating how structural biases can predetermine outcomes. The experience made it clear that even with talent and effort, many are blocked by the simple lottery of the document they hold. For refugees, this simulation is a daily reality. The right to travel hinges on a single, elusive document: the Conventional Travel Document (CTD). It should open doors to study, work, and family, but for many, it feels like an unreliable key.

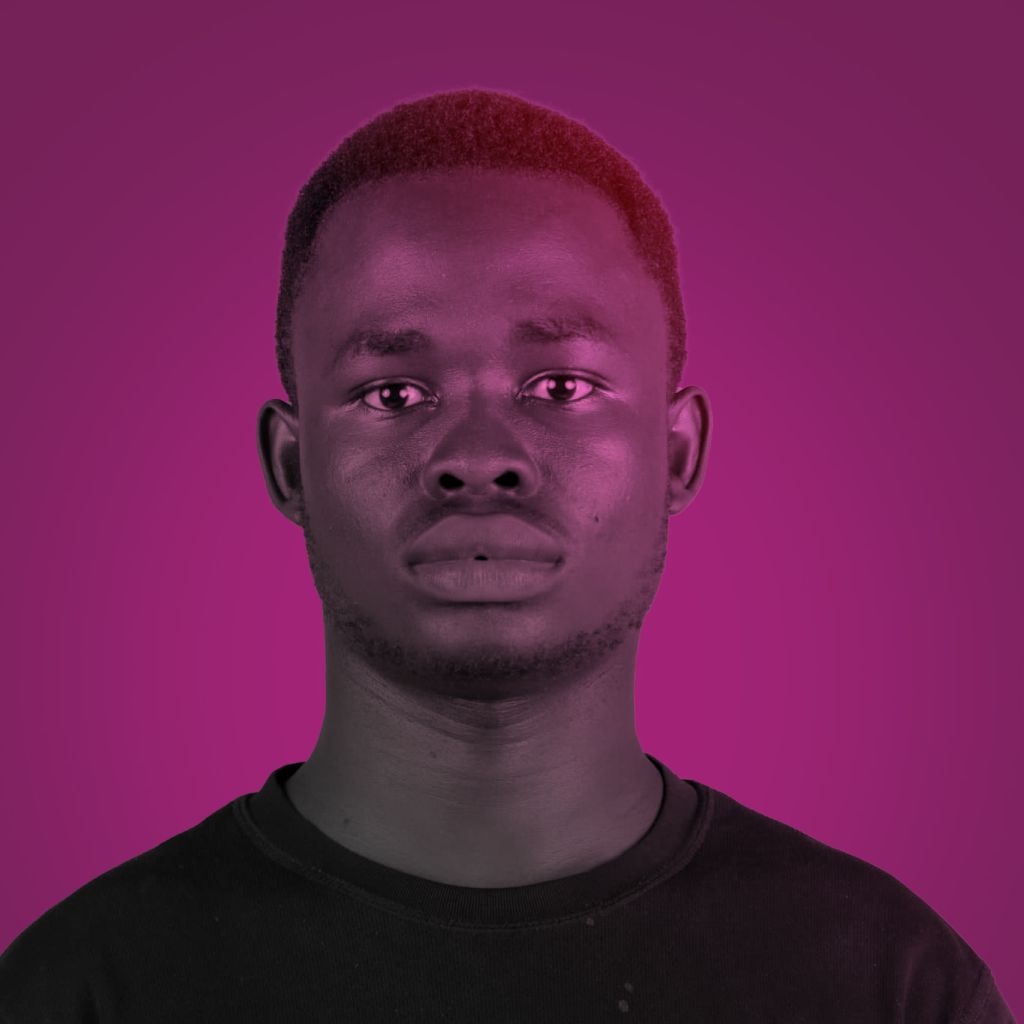

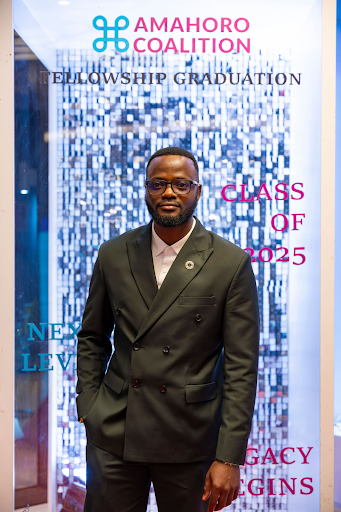

A Tale of Two Journeys: Didier’s Story

Didier Habimana, an Amahoro fellow, and a Rwandan refugee living in Kenya, experienced this firsthand. In 2022, he applied for a CTD, hoping to attend his cousin’s wedding in Zimbabwe and reconnect with family he had not seen in over 20 years. Despite his determination, he was warned that a wedding was not considered a valid reason for travel. Accepted applications are often for high-level forums or scholarships, with family events treated as a lesser priority. After six months with no response, he inquired at the issuing office. An officer found his application in a towering stack of paper and, after making him explain his reasons again, confirmed the rejection, stating, “We don’t accept reasons like weddings or visiting cousins”.

A year later, Didier found a “valid” reason. He was selected for the Amahoro Fellowship that required travel to Ghana. Even then, the document was not ready as the orientation week began, and he had nearly resigned himself to another missed opportunity. He finally received the call to collect his CTD and made it for the last two days of the event.

The moment he held the CTD was indescribable. That single journey transformed his perspective. It allowed him to contribute to conversations on displacement, build a professional network, and showcase his skills in photography and videography. He says, “I no longer view my identity solely through my refugee status, but as a global citizen with the ability and responsibility to contribute anywhere in the world”. His experience shows that when refugees are given mobility, they return with skills and networks that uplift their communities.

I no longer view my identity solely through my refugee status, but as a global citizen with the ability and responsibility to contribute anywhere in the world

Didier Habimana

The Unreliable Key: Deline’s Story

Didier’s friend, Deline Ramiro, another Amahoro fellow, shared that initial feeling of elation upon receiving her CTD. “I believed I was one step closer to global inclusion as a professional, as a woman, and as a changemaker,” she said. However, her story highlights a painful truth: possessing the key does not guarantee the door will open.

In 2023, Deline was invited to the Global Refugee Forum in Geneva; her face and story were even featured on promotional materials. She had the CTD, sponsorship, and an official invitation, yet her visa was denied with only a generic rejection letter. A month later, she was denied a visa for COP28 in Dubai. In 2024, an application for a U.S. visa for another international event was also rejected. The process has taken a severe emotional and financial toll. “Every time I begin the visa process, or even walk into an embassy, my body tenses,” she shared. “My mind fills with fear: Will they see me as less? As a threat? Will they say no again?”.

I believed I was one step closer to global inclusion as a professional, as a woman, and as a changemaker.

Deline Ramiro

Mobility as a Right, not Luck

Friends often tell Didier he is “lucky” to have traveled. But as he reflects, he realizes this should not be a matter of luck; it should be a right. When refugees are encouraged to be self-reliant and innovative, how can they lead when their movement is constantly denied? Deline’s experience underscores what is lost in these denials. “What hurts the most is that the opportunities I missed weren’t just mine,” she says. “I missed them on behalf of my community… I was going to speak for thousands of unheard voices. When I was denied, those stories stayed untold”. Mobility is not a luxury. It is the ability to connect, grow, and represent—a fundamental part of our shared humanity. Refugees are not threats; they are thinkers, artists, advocates, and leaders whose voices need to be heard.