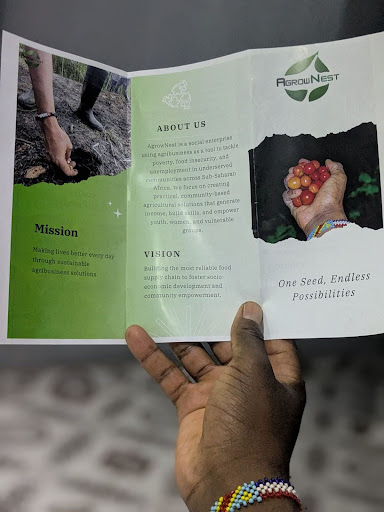

Espoir Bahirwe returned to the Democratic Republic of Congo not on foot, but from the sky. As a remote pilot for a drone company delivering life-saving medical supplies to inaccessible villages, he was a world away from the life he’d known when he fled the conflict in his native Bukavu in 2015. But even as he navigated the skies, he felt a pull back to the earth. The job was impactful, but it wasn’t his mission. That mission is now taking root. Bahirwe is the founder of AgrowNest, a social enterprise using agribusiness to tackle food insecurity and fund educational opportunities in a country where over 20 million people need humanitarian support. It’s the latest chapter in a remarkable journey of a man who used education as an escape route, and is now creating pathways for others to do the same.

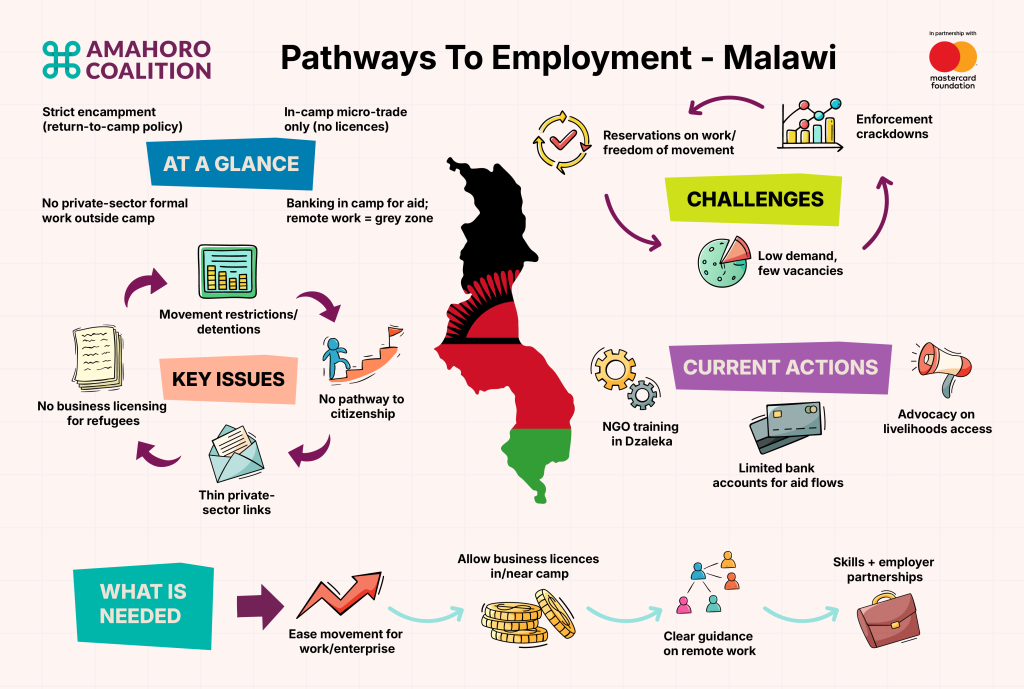

When Bahirwe arrived in Malawi’s Dzaleka refugee camp, he stepped into a pressure cooker. The camp, designed for 10,000 people, was straining under the weight of over 54,000 residents. “The opportunities meant for 10,000 were being shared by more than 50,000,” he recalls. “It was really tough.” He saw higher education as his only way out. He found a diploma program run by Jesuit Refugee Service, but there was a catch: it was taught in English, a language he didn’t speak. Determined, he devised a plan. He volunteered at the institution for nine months, working for free as an academic assistant, immersing himself in an English-speaking environment and building his community involvement. The strategy worked. He was one of just 15 people selected from over 300 applicants for the diploma program.

The opportunities meant for 10,000 were being shared by more than 50,000

Espoir Bahirwe

After completing his diploma and then a degree, Bahirwe’s first instinct was to pay it forward. He co-founded the Advocacy Training and Education Hub (ATE Hub), an initiative to bridge the vast education gap in the camp. ATE Hub provides professional development courses, teaching refugees how to write CVs and market themselves to international employers for remote work, a necessity since Malawian law forbade them from working on-site. To date, the initiative has trained over 700 students. To break down employer stereotypes, ATE Hub developed a toolkit to educate businesses on the value of hiring refugees and started by securing internships. “The employer will have enough time to learn and witness what they are capable of,” Bahirwe explains. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with most employers offering the interns permanent positions afterward.

Despite his success, Bahirwe felt limited by a deep desire to help his home country. The drone pilot job offered a way back to DRC, but he soon founded AgrowNest to make the direct impact he craved. AgrowNest operates on a circular, self-reliant model. The business side focuses on farming to address food insecurity, generating revenue that is then channeled into non-profit initiatives. These initiatives include training local farmers in modern techniques and sponsoring the education of internally displaced children. The Amahoro Fellowship provided the final “boost” he needed to launch, offering mentorship, financial resources, and a vital network of peers across the continent.