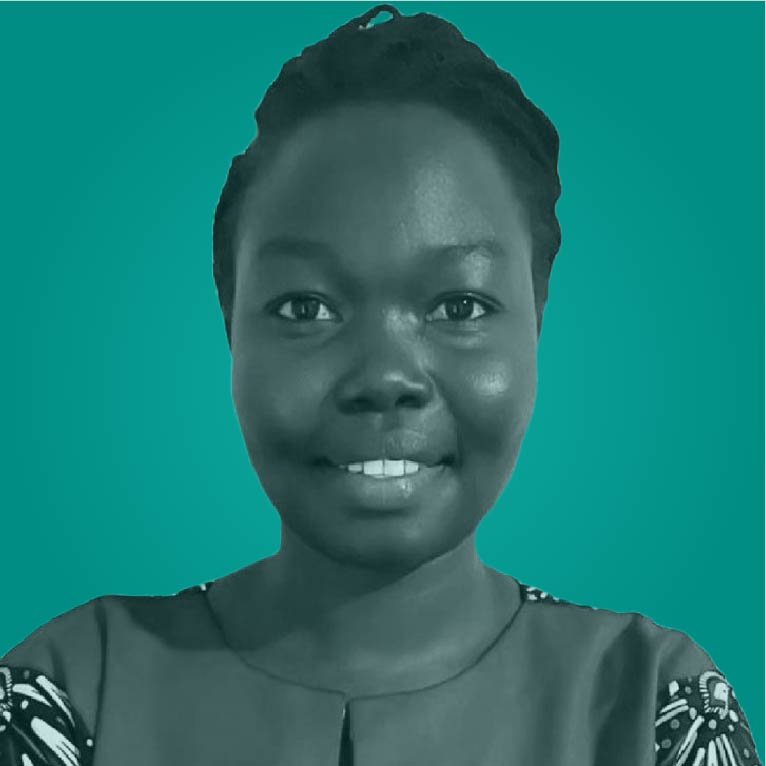

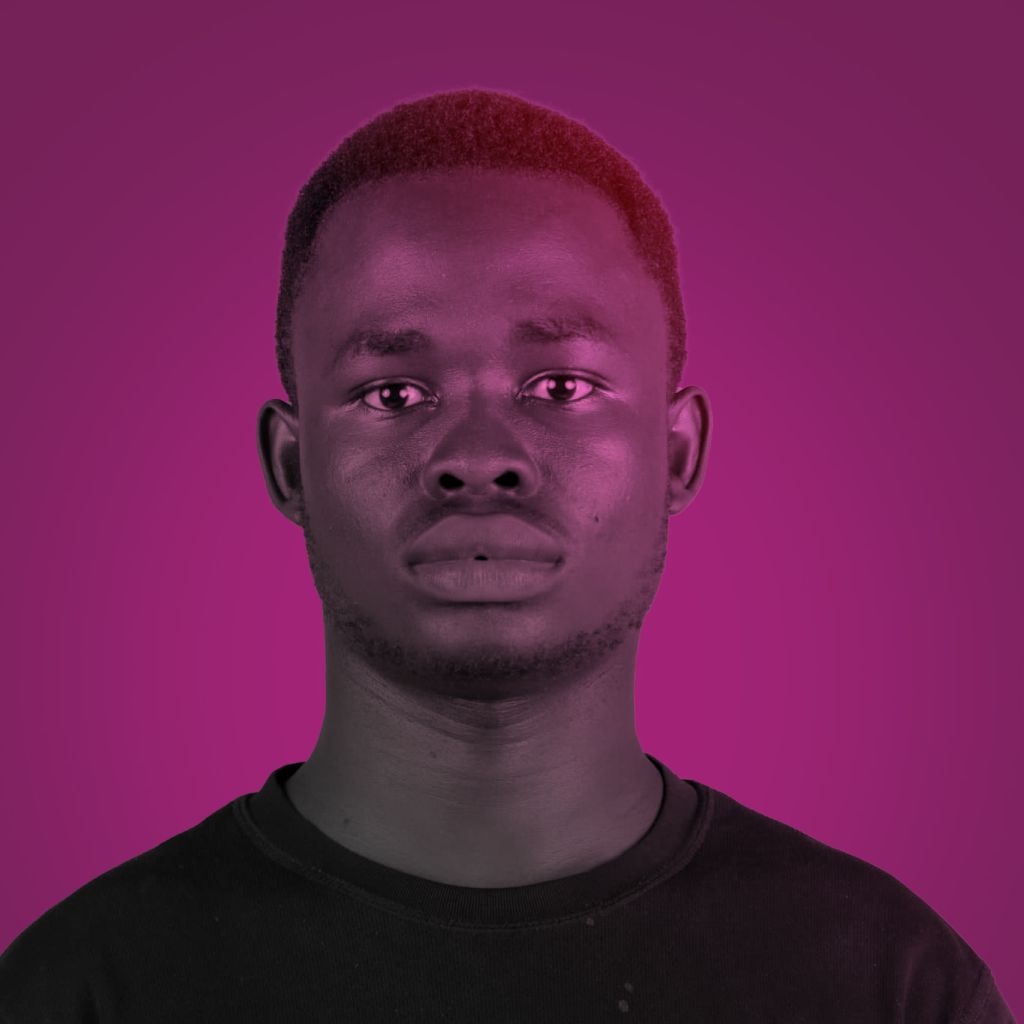

The voices in Nyibol Racheal’s head got so loud in primary six that she decided the only way to silence them was to die. Fleeing war in South Sudan had been one trauma, but losing her sister had unearthed a profound guilt she couldn’t name. A classmate named Ivan saw the darkness gathering around her and saved her life. The adults at her devoutly Christian school had a simpler explanation: “Oh, it’s just the devil”.

For years, that was the only diagnosis she had. But the devil, it turned out, had a clinical name. The revelation came in a psychology class in 2019. As the lecturer spoke, Nyibol felt a light switch on in her mind. “He was giving a name to everything I had always struggled with,” she remembers.

“Oh, mental health or depression or PTSD”. The first thought that followed was not about her own relief, but about the countless others fighting the same unnamed demons. That moment was the start of the Refugee Mental Health Network. But it didn’t begin with a business plan or donor funding. It began with a story.

I need to invest in myself, I am my biggest asset

Nyibol Racheal

Finding an escape in books, Nyibol started writing down her own experiences in a 32-page exercise book. With $2.50, she paid someone to design a cover, printed seven copies, and sold them all. The book became her passport into refugee community spaces, where she saw organizations focused on livelihoods and skills, but a glaring void where mental health support should have been.

“Maybe I could start it,” she thought.

With a Somali friend and just $25 of her own money, she held her first event. In a borrowed community space, they gathered young people to talk—about what mental health meant to them, about trauma, about survival. In a community where sexual violence is used as a weapon of war and seeking help is seen as weakness, these conversations were revolutionary.

The real turning point came in 2024 when she was accepted into the Amahoro Coalition Fellowship. For Nyibol, the fellowship’s stipend was transformative. “Ever since I got into the fellowship, I have been able to buy leadership courses… I’ve been able to afford leadership books that I couldn’t afford before,” she says. She learned that to build a sustainable organization, she first had to build herself.

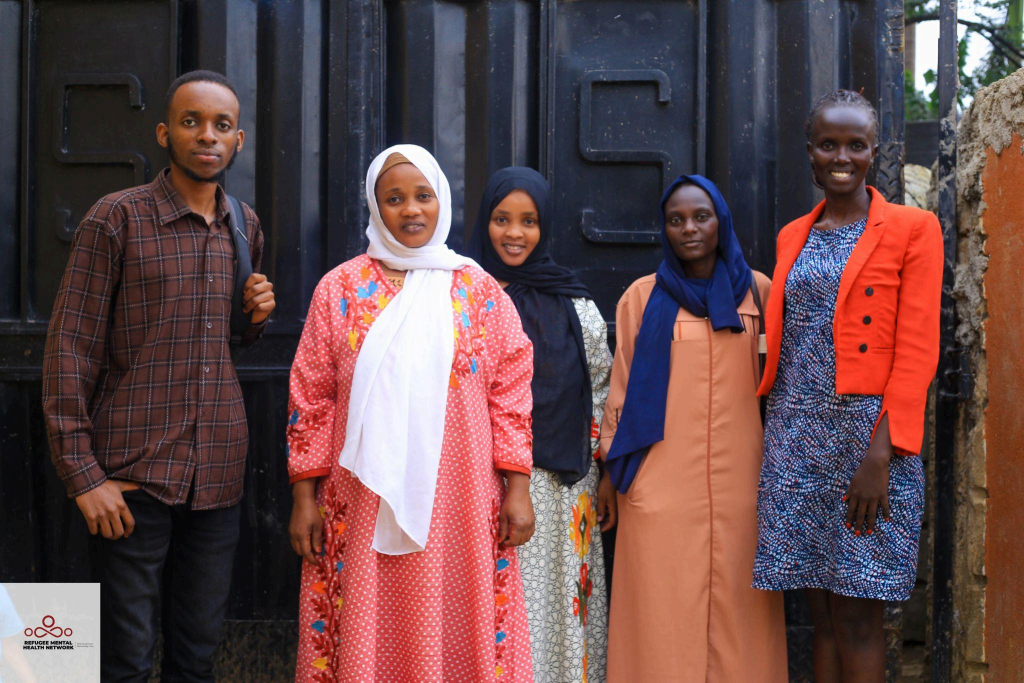

That investment has paid dividends. Since joining the fellowship, the Refugee Mental Health Network has secured a physical office, a symbol of credibility and permanence. Her team has grown from just herself to a team of four.

The impact is best measured in the lives she has changed. She speaks of a mother, a survivor of sexual violence, who was crippled by anxiety for her own daughters’ safety. After an eight-week group therapy program, the woman found a sense of calm she thought was lost forever. “It’s not that the memories of what happened disappear,” Nyibol explains. “It’s just that now they’re able to process and live with it”.

This is Nyibol’s new definition of success. It’s no longer about hitting big numbers. “If you’re able to create lasting change in one person, it’s… it’s worth it”.

Her vision is now as grand as her beginnings were humble. In the next five years, she plans to build mental health hubs in all 13 of Uganda’s refugee settlements, training and employing refugees as mental health caregivers. From there, she’s looking to expand across the Great Lakes region, and eventually, the rest of Africa.

From a girl who was told her pain was the devil to a woman building sanctuaries of the mind, Nyibol Racheal is proving that the most powerful form of aid is not a handout, but a hand to hold in the dark.