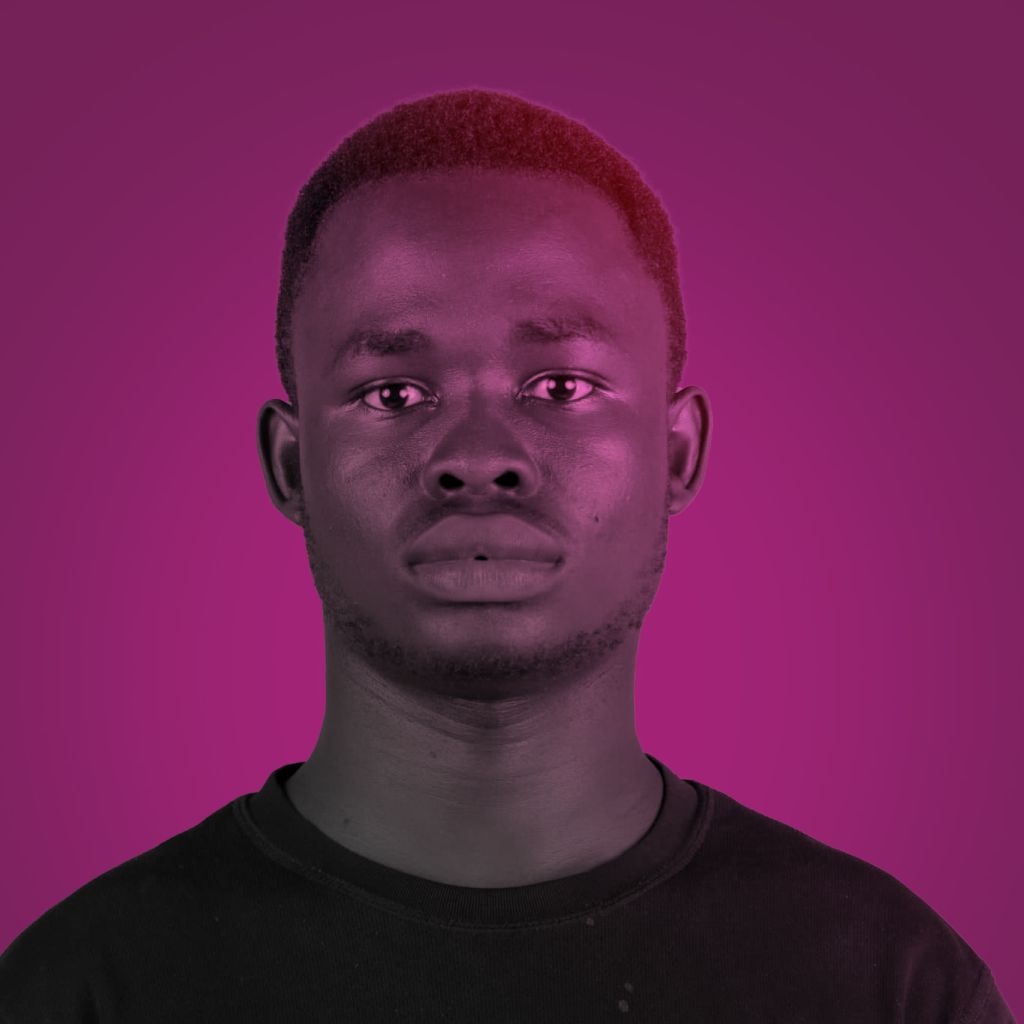

The dust of the Kakuma refugee camp has a way of settling on everything, including dreams. For Kiza Mauridi, a refugee since 1996, that dust was a daily reminder of a life in limbo. He had fled the Democratic Republic of Congo, found a temporary home in Tanzania, and eventually landed in Kenya in 2009, a life punctuated by the sterile acronyms of humanitarian aid. But Kiza was never one to let the dust settle.

After years as a teacher and then an IT coach for a program run by the UNHCR and the Vodafone Foundation, he saw the world changing. The pandemic had forced a global pivot to remote work, and Kiza saw a glimmer of opportunity in the digital haze. “I started noticing that many companies were getting into digital space and adopting the remote work model,” he recalls. For the thousands of young, educated, and idle refugees in Kakuma, this was a potential lifeline.

So, in mid-2022, with little more than a single laptop and a powerful idea, Kiza founded Action for Refugee Learning (AReL). The mission was as audacious as it was simple: to equip refugees with the tech skills they needed to compete in the global marketplace, right from the heart of the camp.

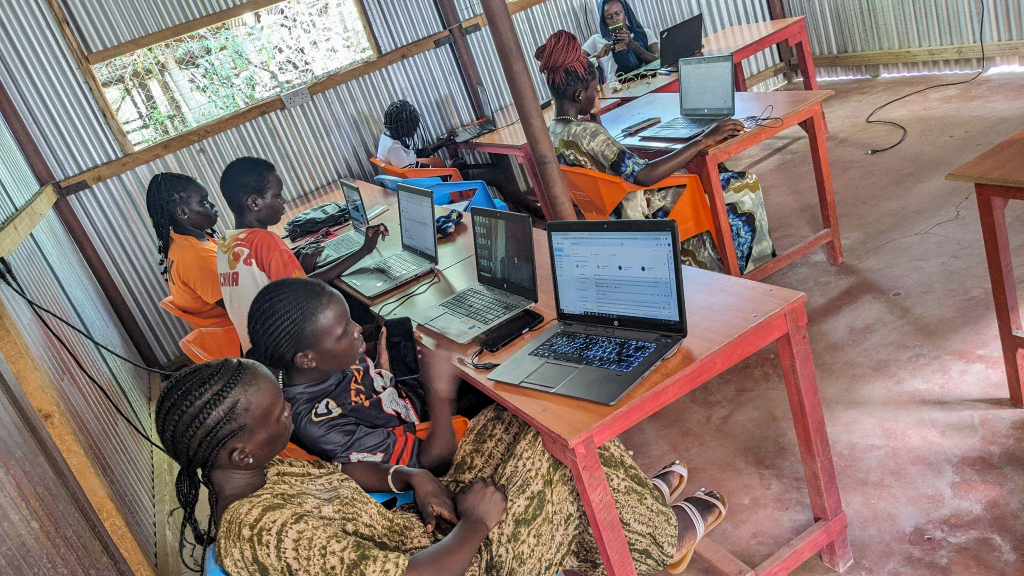

The early days were just sheer will. Kiza poured his own money into renovating a classroom, buying furniture, and even a TV screen for projection. The first students had to bring their own laptops. The internet was slow, the power unreliable, and the instructors were paid in “motivation” rather than a salary. It was a shoestring operation, held together by the force of Kiza’s conviction. But the conviction was contagious. A grant from the Amahoro Coalition in 2024 allowed AReL to buy 30 laptops. Another from WUSC brought in a solar power system and reliable Starlink internet, transforming the organization’s capacity overnight.

Today, AReL is a bustling hub of activity. It has run four cohorts, with 141 students in its third cohort alone, and has graduated between 70-88 students from its programs. The curriculum is a direct response to market demand, offering courses in digital marketing, e-commerce, data analysis, cybersecurity, and full-stack development.

And the results are starting to show. While AReL hasn’t formally started reaching out to companies, some graduates are already securing projects and full-time positions. One is earning 400 Euros a month, another 500 USD. Others are working on contracts for companies in the Netherlands, Uganda, Canada, and Australia.

For Kiza, this is more than just a job creation scheme. It is a direct challenge to the cycle of dependency that defines life in the camp. “I see it as a solution… as the current situation in Kenya with the donor fund shrinking,” he says. “I’m seeing it to be one of the workable solutions…providing the skills and then trying to talk to the private sectors to get them into employment.

“His call to action is a powerful one. To his fellow refugees, he says, “Don’t take the program that we’re providing for granted.” To private sector partners, he offers a ready-made pipeline of talent, supported by a unique mentorship model that pairs graduates with industry professionals. To investors, he pitches a vision of a “small Silicon Valley” in Kakuma, a modern tech college that can develop solutions for Africa’s own problems.

In a world where the narrative of the refugee is too often one of passive victimhood, Kiza Mauridi is rewriting the script. He is proving that with the right tools and a little bit of audacity, even the most desolate of landscapes can become fertile ground for innovation. He is not just teaching code; he is coding a new kind of future.