Three reflections Amahoro Coalition shared with world leaders in Davos

By Isaac Kwaku Fokuo, Curator at Amahoro Coalition

The air in Davos is famously thin, but the way we speak about global crises often feels heavy with surprise. This year, however, the conversations were less about shock and more about confirmation. What many have sensed for some time is now unmistakable: the world has entered a fragmented age of competition, shaped by geopolitical rivalry, economic nationalism and deepening polarization. Inequality is widening, trust in institutions is eroding, and the social contract feels increasingly fragile. What once appeared as a series of isolated shocks now looks more like a permanent condition.

It was against this backdrop that I joined a high-level conversation on the role of the private sector in humanitarian settings organized by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) on the margins of the World Economic Forum in Davos. The mood in the room was not alarmist, but sober. There was a shared recognition that the humanitarian system, as currently designed, is no longer aligned with the realities of the twenty-first century. Emergencies are no longer brief interruptions to stability. For millions of people, crisis is the status quo.

The numbers reinforce this reality. Official development assistance is declining, even as the duration of displacement continues to lengthen. What were once described as temporary camps have evolved into permanent urban settlements. “Short-term response” has quietly become a multi-decade reality. Across Africa, from the Sahel to Sudan to the Great Lakes, displacement is not an abstract policy challenge. It is a lived, generational experience.

At Amahoro Coalition, our work begins with a simple conviction: displaced people are not defined by their vulnerability, but by their potential. No one aspires to depend on aid indefinitely. Yet much of the global humanitarian system remains structured around sustaining survival rather than enabling opportunity. Lifesaving assistance remains essential in moments of acute crisis, but survival alone cannot be the horizon for people who have been displaced for years, or even decades.

The first reflection we shared in Davos is that humanitarian action must be complemented, not replaced, by private-sector leadership.

Too often, business is invited into this space only as a fallback, framed narrowly through corporate social responsibility. That framing underestimates what markets can uniquely contribute. Aid can feed people. Only jobs can restore agency, dignity, and long-term stability. The private sector does not need to become a humanitarian actor. It needs to become a permanent employer.

The second reflection is that Africa sits at the center of the global economic future.

Within two decades, one in every three young people on the planet will be African, and a significant portion of this generation is currently living in displacement. To treat this population as a burden is a strategic mistake. They represent one of the world’s largest untapped sources of talent, labor, and entrepreneurship. The real question is not whether displaced people can contribute, but whether our systems will allow them to.

Encouragingly, several African governments are already shifting their policy frameworks to recognize displaced people as economic actors rather than passive beneficiaries. But policy alone does not create prosperity. Inclusion only becomes real when markets respond, when businesses invest, and when employment opportunities exist at scale. Jobs, not just programs, are what ultimately sustain peace and growth.

The third reflection we shared is that the private sector must move beyond small pilots toward systems-level transformation.

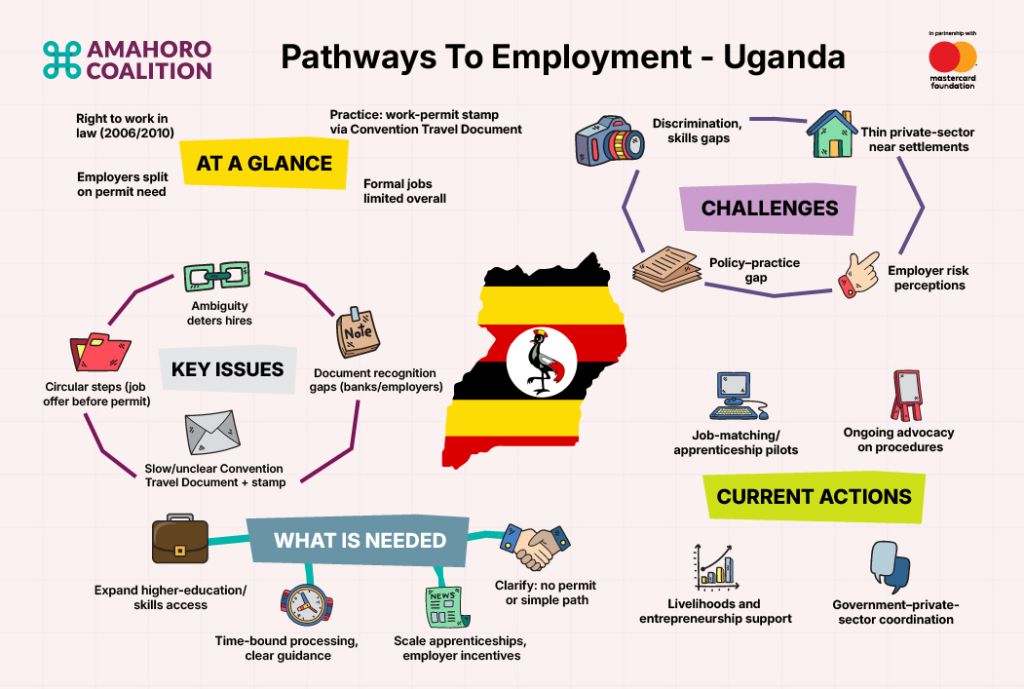

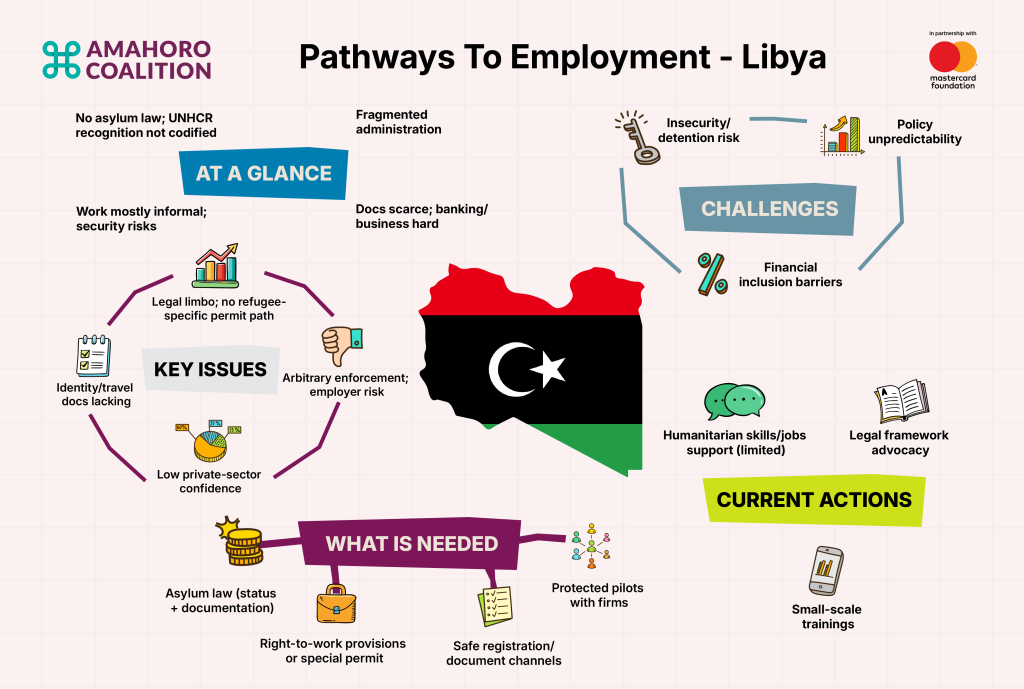

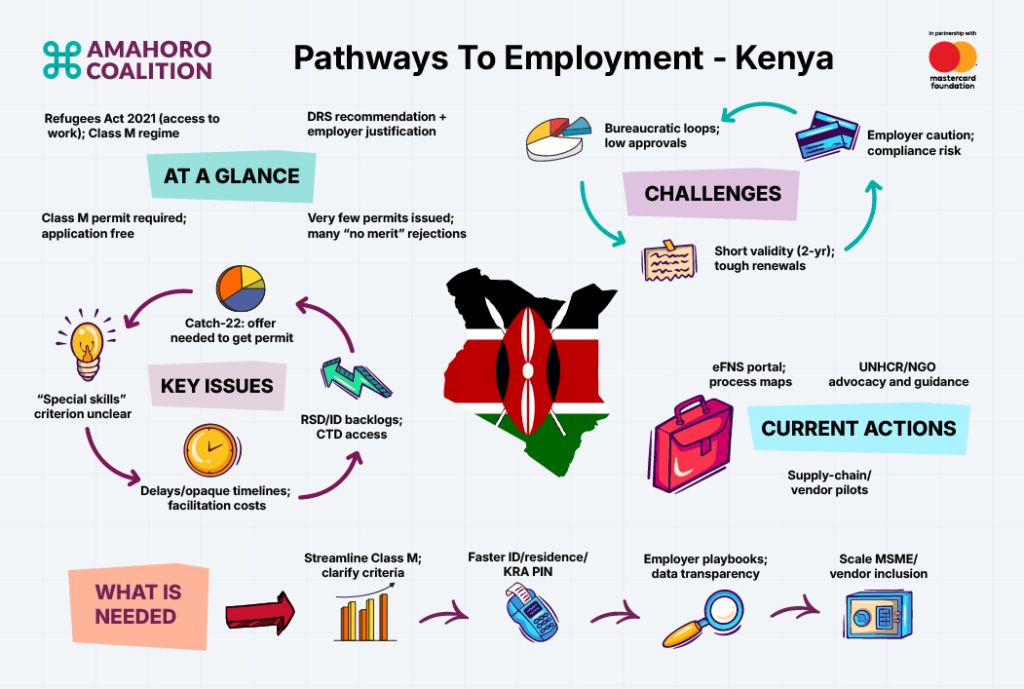

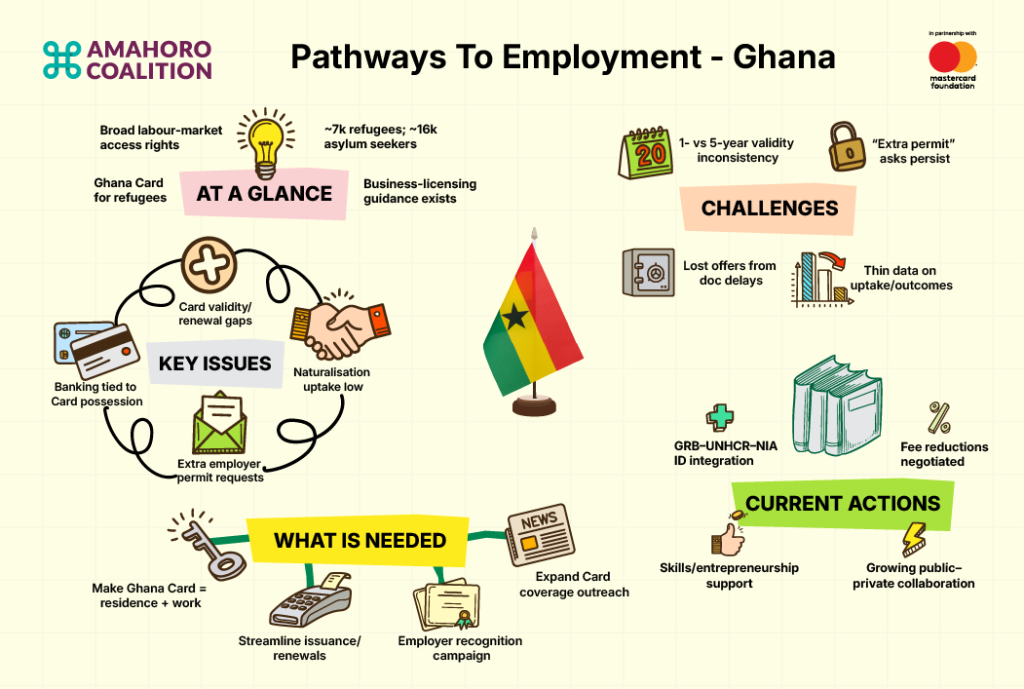

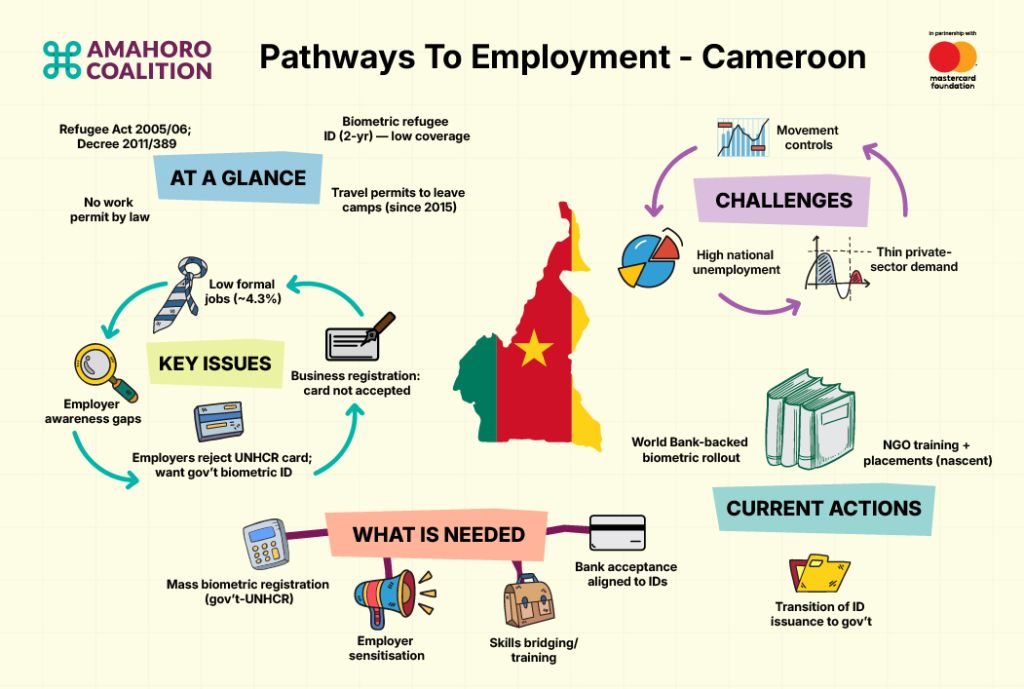

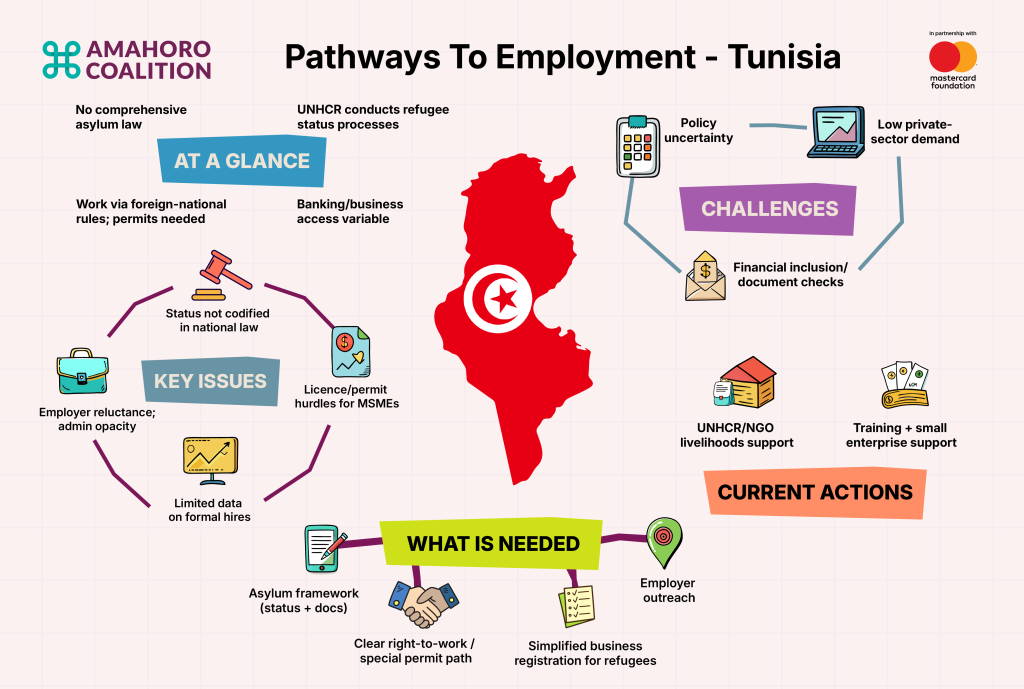

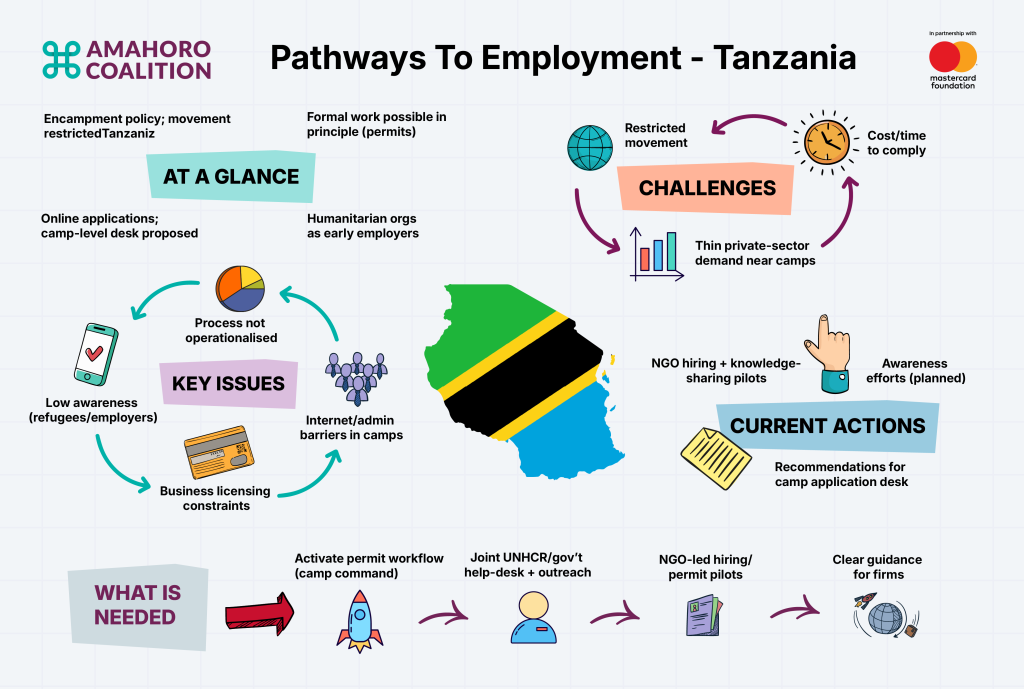

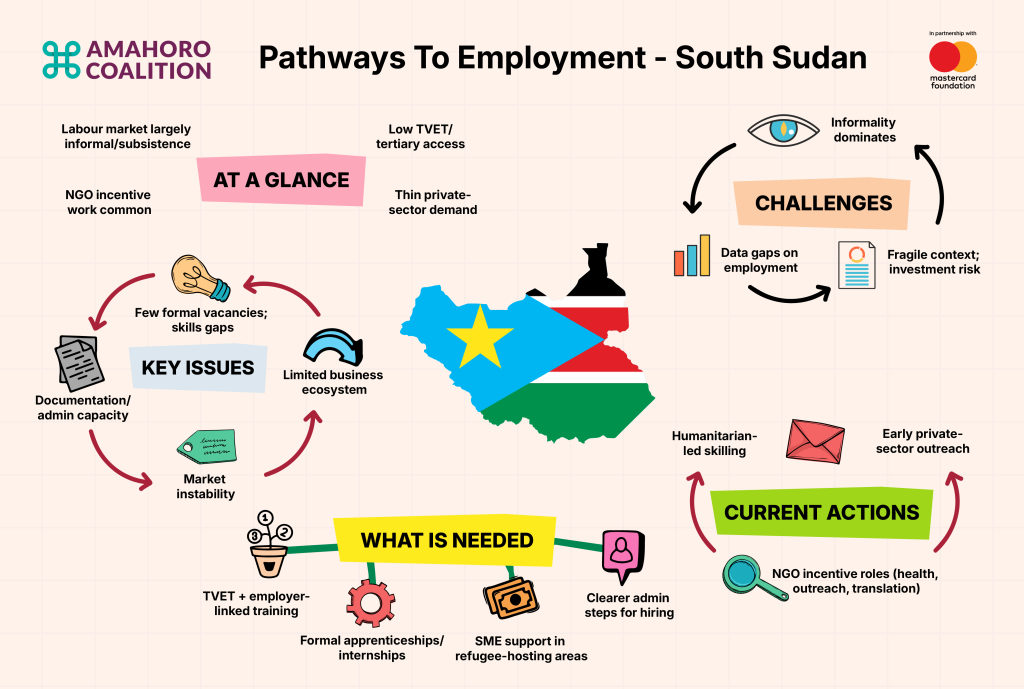

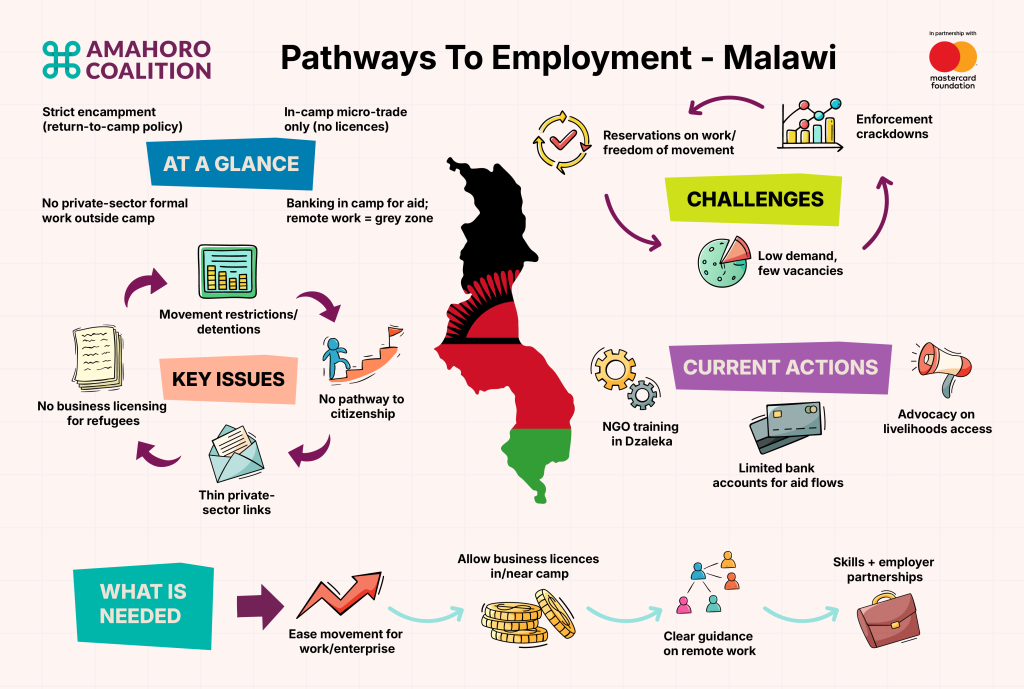

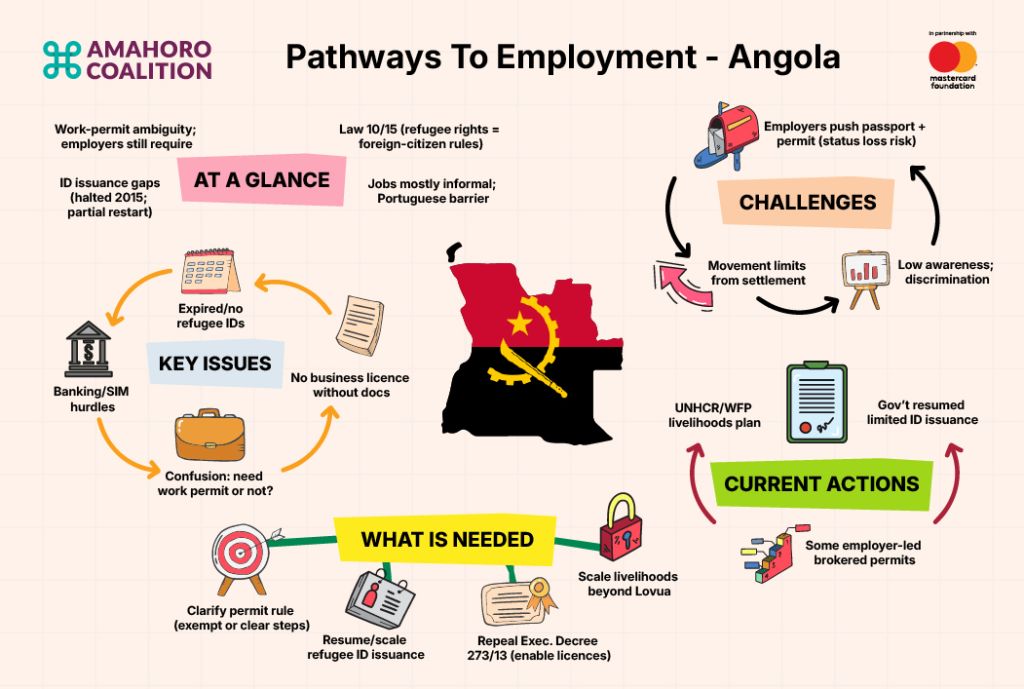

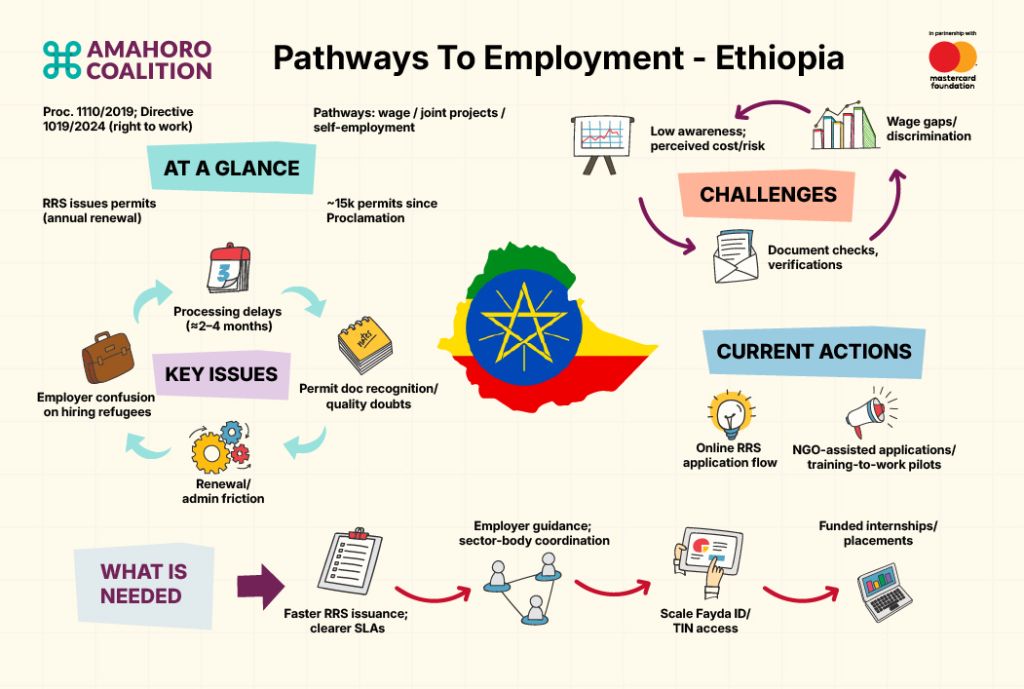

Through our Pathways to Employment research across fifteen African countries, we found consistent evidence of what many practitioners already know: the ecosystem is suffering from pilot fatigue. Small projects may inspire hope, but they do not change outcomes for millions. What is needed is alignment across labor markets, legal frameworks, financing models and long-term private investment.

Nigeria offers a powerful illustration of what this shift can look like. In a country of roughly 240 million people, with a median age of just eighteen, displacement driven by conflict and climate shocks represents a massive loss of human capital. Instead of asking how to feed displaced communities indefinitely, we partnered with the Bank of Agriculture to ask a different question: how can we employ them? The result is an ambitious plan to create 200,000 jobs across the agricultural value chain, spanning production, processing, logistics, and market access. The premise is simple but transformative: inclusion is not charity, it is a growth strategy.

The current moment demands more than incremental change. When displaced people are integrated into formal economies, businesses expand, workforce gaps shrink, and the pressures driving irregular migration ease. This is not only a humanitarian imperative, but an economic and political one. The invitation to the private sector must shift from charity to strategy.

Displacement does not have to mean permanent dependency. If we move from portions to payrolls, from pilots to systems, and from short-term relief to long-term economic integration, we can transform what is often framed as a “refugee crisis” into a catalyst for stability, productivity, and shared prosperity. That is the opportunity before us, and the responsibility we can no longer afford to postpone.